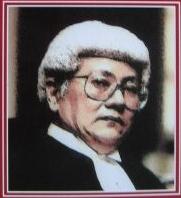

LoyarBurok is pleased to present its exclusive interview in five parts with the incorrigible, irrepressible and inimitable Chan Nyarn Hoi, Malaysia’s most famous retired Court of Appeal judge.

For those of you who faithfully follow LoyarBurok or the new media establishments like Malaysiakini or The Malaysian Insider, NH Chan needs no further introduction or biography. If you don’t know of it, and since we are LoyarBurok, we will not trouble ourselves to do so except to exhort that you stop reading at once and get ye hence to a proper bookstore (that means Kinokuniya and any MPH or Borders that is larger than 2,000 square feet) and purchase his latest edition (2nd) of ‘Judging the Judges’.

As NH Chan has been terribly generous with his responses to our questions, as he has been with his deserving criticism of the judicial decisions emanating from the judiciary, we have decided to break up the interview into five parts which would be published every alternate day for ease of reading and consideration. The questions were crafted by the LoyarBurok team with the powerful inspiration of Lord Bobo. So without further ado, we bring you The Loyarburok Interview with NH Chan.

If you had not been a lawyer, what would you be doing now?

I really don’t know. In the early fifties, when I was nineteen years old, I wanted to be a fighter pilot. My RAF flying instructor used to enthuse over my natural ability to fly – he believed that I was going to be an ace. I was in the Malayan Auxiliary Air Force in Penang at Bayan Lepas – my friend Arul and I, and in Selangor Ajaib Singh, were the only ones in the MAAF who later became lawyers. The late Ajaib Singh became a judge of the Federal Court and Arul is a maritime arbitrator and lawyer in Singapore.

I could even do a downwind turn at tree top height without committing the dangerous error of applying top rudder. My instructor told me afterwards that most novice pilots would instinctively apply top rudder which could be fatal at such a low altitude as that would sideslip the aircraft into the ground, snapping a wing in the process – because an aircraft has to bank to make a turn one wing would be lower than the other – and burying its nose in the earth killing its pilot and crew. That actually happened in Selangor where Ajaib Singh once used to fly. The papers at the time blamed it on a wing falling off – which was impossible anyway as even in the tightest of turns there was not enough G-force to snap a wing of a Harvard which was an aerobatic trainer. But to us in the know, the two pilots in the Harvard trainer were killed because top rudder was applied instead of bottom rudder.

Before I went solo I used to be able to do impeccable three point landings. I was one of those people who could fly by the seat of the pants. Arul told me that he went up in his in-laws’ Tiger Moth in Switzerland not too long ago and he was surprised to find there was no artificial horizon in the instrument panel. It took him awhile to adapt to flying without the basic instruments. He was anxious about stalling the aircraft because he would not know if he was climbing and losing airspeed. I told him that the RAF airplanes that we used to fly had a full complement of instruments but civilian aerobatic planes – which were also capable of inverted flight – do not have them. One way is to keep an eye on the airspeed indicator and know the stalling speed of the aircraft. Another way is to fly by the seat of one’s pants or you could anticipate a stall when the upper leading edge wing slat of the Tiger Moth would open because of the increased angle of attack as it approaches close to stalling speed.

I went solo in six and a half hours. But by then I knew how to recover from a spin, to loop and even perform an Immelmann – in days gone by those were essential manoeuvres in a dogfight. But my late father opposed my weekend stint and sent me to England where I read law. He demanded to know why I wanted to be a fighter pilot – because I want to be a war hero was my reply. There is no war in Malaya, he retorted. It was during the Emergency and the fight against the communist insurgents – they were skirmishes against the bandits in rubber plantations and in the jungles of peninsular Malaya – was a land battle. It was not even a war. The only aggression I encountered in the air was when we were invited by the RAAF based at Changi, Singapore – on board their Lincoln bombers (the Lincoln’s precursor was the renown Lancaster of WW2) – to join them on a bombing run over the Pahang jungle near the Kuala Lipis area. After dropping their bombs the bombers went down to tree top height to strafe the jungle – I thought to myself, poor monkeys. We even flew over the camps of the security forces operating in the area to greet them. The camaraderie among fighting men were amazing.

I became an advocate and solicitor instead.

In the early years of legal practice I took part in motor racing. I had raced at Batu Tiga – even at the Tunku Abdul Rahman circuit races before that. But circuit racing was too expensive for a budding lawyer to afford, so I switched to motor rallies.

I don’t play golf. But a close friend who is a golfer tells me that golf is just as dangerous. You could be struck by lightning or by a golf ball. For this to happen is fortuitous. Uncertainty doesn’t appeal to me. I must know what to do beforehand.

A fighter pilot, in order to survive in a dogfight, must know what to do beforehand, so that he could execute the manoeuvres as second nature. Similarly, in motor racing you must know all about the limits of adhesion – different bends have a different limit for each bend; how to correct or get out of a skid; about braking distances; and about over-steer and under-steer which will affect the handling characteristics of different types (those with the engine in front or behind; front wheel or rear wheel driven) of motor vehicles. The Mini Cooper under-steers because it is a front wheel driven car. But most other cars over-steer because they are rear wheel driven.

A long time ago, there was an incident where my wife was driving. She was approaching a left hand bend at slightly above 70 mph. I pointed out to her that that particular bend could only be taken at 70 mph. The next moment I felt the rear wheels breakaway.

So I yelled, “If you want to stay alive jam on the brakes and turn the steering wheel to the left.”

She did as she was told to do. I also helped by grabbing the steering wheel and turning it to the left. The car spun on its axis in the middle of the road and came to a stop. Fortunately there was no oncoming traffic as it was late at night. If she had not done as she was told the car would have skidded off the road and wrapped itself round a tree.

We survived because I knew exactly what to do beforehand. If I were driving, I would have corrected the skid in the normal way – opposite lock, lift off the throttle pedal just enough to allow the rear tyres to regain adhesion to the road and then gently accelerate out of the skid. But it was my wife who was driving and I had only a split second to react. The only way out of the dangerous situation was to make the car spin on its axis in the middle of the road in order to prevent the car leaving the road and killing both of us – Jimmy Doolittle who led the bombing raid on the Japanese mainland shortly after Pearl Harbour called this a calculated risk. If I didn’t know what to do beforehand the disaster could not have been averted because no one could react instantly when confronted with such danger, unless he knew beforehand what to do.

Likewise, a judge must know what to do beforehand – he must know basic law beforehand so that he could give the correct decision immediately. There is no need to write a lengthy judgment on known law – known law is elementary law. It is not the length of the judgment that matters. If the correct answer is going to be in one sentence or in one or a couple of paragraphs or even on one page, so be it – that is the judgment.

HS Ong used to do it in a few short sentences. He used to clear many cases before lunch. Unless he had a trial, in which case a certain amount of time had to be spent for evidence to be adduced. Now you know why Lim Kean Chye said that he never brings any books when he appeared before me. Lord Denning tells us about the best way of getting at a correct decision, which is also my way of doing it. He wrote about it in The Family Story, page 205:

To my mind the best way of getting at a correct decision is that which was pursued by Socrates some 2,400 years ago. He did it by word of mouth – by asking questions – and getting the answers he wanted. I will give you an instance from The Republic of Plato (Jowett’s translation):

“Socrates: Do you admit that it is just for subjects to obey their rulers?

Thracymachus: I do.

Socrates: But are the rulers of states absolutely infallible, or are they liable to err?

Thracymachus: To be sure, they are liable to err.

Socrates: Then in making their laws they may sometimes make them rightly, and sometimes not.

Thracymachus: True.”

So Socrates had made Thracymachus agree that it is common ground that rulers are fallible. He did it orally – by asking questions – and getting the answers he wanted. This is also my way – which is confirmed by Lord Denning as the best way – of getting at a correct decision. Here is a hypothetical example of how I used to do it when I was a serving judge:

Judge: You are asking for a declaration, is this your point?

Counsel: Yes. The Speaker had acted outside his authority under the Standing Orders of the Assembly when he suspended my clients from attending the Legislative Assembly.

Judge: But what about Article 72(1) of the federal Constitution which says, “The validity of any proceedings in the Legislative Assembly of any State shall not be questioned in any court”? As a lawyer you should know “shall” means “must”.

Counsel: Article 72(1) must be read as being subject to the existence of a power or jurisdiction, be it inherent or expressly provided for, to do whatever that has to be done. The Court is empowered to ascertain whether a particular power that has been claimed has in fact been provided for.

Judge: But the Federal Constitution is the supreme law of the land. It binds the courts, even Parliament itself, until it is changed by Parliament with a two-thirds majority. What happened within the Assembly cannot be questioned in any court.

Counsel: Parliament makes the Law and the Courts interpret it.

Judge: Surely you don’t interpret the obvious where there is no ambiguity. The words in Article 72(1) mean exactly what they say. Even a child could understand that. And the words in Article 72(1) say that the validity of the proceedings which took place in the Legislative Assembly could not be questioned in any court.

Counsel: I thought it is for the courts to say what the law is. They have the power to interpret the law.

Judge: You are sorely mistaken. True enough when it comes to the common law. It is not so when it is a statute. The courts will interpret a statute only when there is an ambiguity. Not when the words are clear and they are not capable of another meaning. You can’t put words into a statute that are not there.

Counsel: As the court pleases.

Judge: If that is all that you are able to say, here is my decision. I don’t need to hear you Mr T (turning to and addressing Counsel for the Speaker).

Judge: Even when the Speaker has no power to suspend anyone in the Legislative Assembly, it was done by the Speaker in a proceeding in the Legislative Assembly. Article 72(1) of the Federal Constitution has decreed that “The validity of any proceedings in the Legislative Assembly of any State shall not be questioned in any court”. The validity of the suspension of these members of the Assembly by the Speaker during a proceeding in the Assembly could not, therefore, be questioned by this, or any, court. Article 72(1) of the Federal Constitution must be obeyed to the letter. As Lord Denning once said, “No matter how unreasonable or unjust it may be, nevertheless, the judges have no option. They must apply the statute as it stands”. I apply Article 72(1) of the Federal Constitution as it stands and I dismiss the application for a declaratory decree.

This is it. There is no need to write a judgment at all. My secretary would have taken it down in shorthand and she would let counsel have a copy of the notes of the proceedings when counsel asks for them. A written decision is unnecessary because it is made on known law. This is a decision on obvious law. Even school children could understand it.

Incidentally, the plural of “counsel” is “counsel”; it is not “counsels”. Surprisingly, many of our judges don’t know that the plural of “counsel” is “counsel”.

There is no such word as “counsels” in the English language.

Hello. I feel a bit of a fraud commenting here, because I'm not a law student nor am I connected with the law.

I was just wondering if Chan Nyarn Hoi was in the MAAF at the same time as my father, who was the CO of RAF Penang from 1954 to 1957 – Flt Lt James (Jimmy) Davie. It might be possible that he was his flying instructor since he was teaching MAAF flyers, beginning on simulators and then going on to the real thing. He was a Spitfire pilot during the war (WWII that is) and was posted to Malaya with my mother and me (aged 6-8) in 1954. I don't know if there is any way of finding out. I certainly don't know how to. I was rather curious, reading this account.

I can remember a reasonable amount, including the visit of Tunku Abdul Rahman who had just been made the First Prime Minister (57). My father showed him the work he was doing and show him around the place. I was presented to him and I thought he was a really lovely man and even at aged 8 was surprised at his kindness, considering his obvious importance.

Hi Sheila,read this post today,i had an uncle who was a flying officer with MAAF,unfortunately he died in a plane crash(Harvard FX 282) in Tiger Lane,off Ipoh airport on 3rd sept 1952,the commanding officer for MAAF that time was Flt Lt De Pass

If you had not been a lawyer, what would you be doing now?

(I really don’t know. In the early fifties, when I was nineteen years old, I wanted to be a fighter pilot. My RAF flying instructor used to enthuse over my natural ability to fly – he believed that I was going to be an ace. I was in the Malayan Auxiliary Air Force in Penang at Bayan Lepas – my friend Arul and I, and in Selangor Ajaib Singh, were the only ones in the MAAF who later became lawyers. The late Ajaib Singh became a judge of the Federal Court and Arul is a maritime arbitrator and lawyer in Singapore.)

>>>(This man had not read this portion (of the interview with Justice NH Chan, almost missed the interviewer’s question above), being still absorbed in the Judge’s recent book. The Malayan Auxiliary Air Force must have been the precursor here to the Royal Malaysian Air Force, stationed at Bayan Lepas beside KL. Definitely, Kepala Batas, Alor Star would not have been left out.)

(I could even do a downwind turn at tree top height without committing the dangerous error of applying top rudder. My instructor told me afterwards that most novice pilots would instinctively apply top rudder which could be fatal at such a low altitude as that would sideslip the aircraft into the ground, snapping a wing in the process – because an aircraft has to bank to make a turn one wing would be lower than the other – and burying its nose in the earth killing its pilot and crew. That actually happened in Selangor where Ajaib Singh once used to fly. The papers at the time blamed it on a wing falling off – which was not possible anyway as even in the tightest of turns there was not enough G-force to snap a wing of a Harvard which was an aerobatic trainer. But to us in the know, the two pilots in the Harvard trainer were killed because top rudder was applied instead of bottom rudder.)

>>>(That is in a truth a fighter crew type turning at a landing – tree top height at downwind turn – would not leave much height at base turning (into) final. In case the Judge had not described applying top rudder here (at this point), as committing a dangerous error, this person here would have instinctively thought applying top rudder would be the appropriate procedure. Rudder application here together with timely aeileron turn would here cos a controlled (not geater than) 2-degree turn. In such a movement, a left (banking) turn would here cos the left wing to drop (simultaneously producing yaw movement when rudder not applied. Instinct would tell a flght crew here that applying top rudder would counter the leftward sideslip towards the lower left wing.

Finding just not sufficient (pun not intended), the following here this man found in a reliable book on flying:

The term skid denotes a particular type of slip that occurs when the airplane is in a bank and the uncoordinated airflow is coming from the side with the raised wing. Typically this happens because you have tried to speed up a turn using “bottom rudder”, that is, pressing the rudder pedal on the same side as the lowered wing.

We use the term proper slip to denote a slip that is not a skid.

If you have plenty of airspeed, the aerodynamics of a skid is the same as the aerodynamics of a proper slip. In both cases there is air flowing crosswise over the fuselage. However, you should form the habit of not skidding the airplane, for the following reason.

If the aircraft stalls, any slight crosswise flow will cause one wing to stall before the other. In particular, having the rudder deflected to the right means the aircraft will suddenly roll to the right. If the aircraft is in a 45 degree bank to the right and rolls another 45 degrees in the same direction (because you were applying right rudder pressure), it will reach the knife-edge attitude (wings vertical). Done in a opposite manner, you could hold top rudder (still holding right rudder but banking to the left this time), a sudden roll of 45 degrees would leave you with wings level (which is a big improvement over wings vertical).

If the wings are level, you can make a proper slip to the left or to the right; a skid is impossible by definition.

* Bottom Rudder: Right vs. Wrong

It is appallingly easy to set up a situation that leads to an unintentional skid. Suppose you are ready to make a left turn from base to final. You start the turn improperly, by applying a little left rudder. The crosswise airflow pattern acting on the dihedral of the wings will cause the airplane to bank to the left and make a relatively normal turn in the desired direction. You absent-mindedly maintain the left rudder pressure, so the bank continues to steepen. You decide to apply right aileron to prevent further steepening of the turn. That’s all you need: you are in a skidding left turn, holding left rudder and right aileron, at low altitude. If you stall, you’ll never be heard from again.

Hope here this answer is enough.)

(Before I went solo I used to be able to do impeccable three point landings. I was one of those people who could fly by the seat of the pants.)

>>>(That would mean employing the (human nervous system’s) proprioception (position sense received at every of the locomotor system’s joints) sense in addition here to vision senses, especially during VMC flight. He mention not another sense here cos there is more not.)

(Arul told me that he went up in his in-laws’ Tiger Moth in Switzerland not too long ago and he was surprised to find there was no artificial horizon in the instrument panel. It took him awhile to adapt to flying without the basic instruments. He was anxious about stalling the aircraft because he would not know if he was climbing and losing airspeed.)

>>>(Meaning this airplane would not be able to be flown in IMC outside IFR. During VMC, the true horizon (in relation the airplane’s nose) would provide what the missing instrument, if present, would provide.)

(I told him that the RAF airplanes that we used to fly had a full complement of instruments but civilian aerobatic planes – which were also capable of inverted flight – do not have them. One way is to keep an eye on the airspeed indicator and know the stalling speed of the aircraft. )

>>>(Barnstormers & fighter pilots would not involve in aerobatics outside VMC. Definitely, the ASI is vital.)

(Another way is to fly by the seat of one’s pants or you could anticipate a stall when the upper leading edge wing slat of the Tiger Moth would open because of the increased angle of attack as it approaches close to stalling speed.)

>>>(This way, a early alert seem to be receivable (instead of relying on the tone of the sound of the engine, and the general instability of the airplane fast-approaching stall.)

(I went solo in six and a half hours. But by then I knew how to recover from a spin, to loop and even perform an Immelmann – in days gone by those were essential manoeuvres in a dogfight.)

>>>(Definitely, impressive achievement. This Immelmann here would seem to be (a combat manouevre) involving half-loop followed by correcting the inverted position, generally performed here to get behind enemy aircraft (in a dog-fight). That word is not found in a dictionary. This man’s experiences in aerobatics is generally not more than as passenger in the (Scottish made) Bulldog, the (Italian made) MB 339, the (USAF) A4 Skyhawk (alongside RMAF pilots), & a T38 a time with a USAF fighter crew.)

>>>(Combat manouevres (to be used in cannon dog -fights) have reduced much in importance presently because of the presence of (air to air) missiles – both heat-seeking (range ½ mile – 10/15 miles, and radar-controlled (range 10 -60 miles). A Fighter airplane today is not less than a platform for launching missiles. The F6D-1 Fighter jet at around 70’s completely did away with cannons, not more than launching missiles. But, subsequent designs still felt the presence of cannon a necessity (in providing superiority, dog-fights not a rarity even with missiles on board, in a order.)

( But my late father opposed my weekend stint and sent me to England where I read law. He demanded to know why I wanted to be a fighter pilot – because I want to be a war hero was my reply. There is no war in Malaya, he retorted. It was during the Emergency and the fight against the communist insurgents – they were skirmishes against the bandits in rubber plantations and in the jungles of peninsular Malaya – was a land battle. It was not even a war. The only aggression I encountered in the air was when we were invited by the RAAF based at Changi, Singapore – on board their Lincoln bombers (the Lincoln’s precursor was the renown Lancaster of WW2) – to join them on a bombing run over the Pahang jungle near the Kuala Lipis area. After dropping their bombs the bombers went down to tree top height to strafe the jungle – I thought to myself, poor monkeys. We even flew over the camps of the security forces operating in the area to greet them. The camaraderie among fighting men were amazing.)

>>>(True, a greater portion of the Emergency skirmishes were land-based, but fighter-ground attacks were a rarity not. Poor Communists!)

(I became an advocate and solicitor instead.)

>>>( Air Force’s loss, a gain to law practice & Judiciary.)

(In the early years of legal practice I took part in motor racing. I had raced at Batu Tiga – even at the Tunku Abdul Rahman circuit races before that. But circuit racing was too expensive for a budding lawyer to afford, so I switched to motor rallies.

I don’t play golf. But a close friend who is a golfer tells me that golf is just as dangerous. You could be struck by lightning or by a golf ball. For this to happen is fortuitous. Uncertainty doesn’t appeal to me. I must know what to do beforehand.)

>>>(Try cricket. Tremendous forethought is required in this cavalier game.)

(A fighter pilot, in order to survive in a dogfight, must know what to do beforehand, so that he could execute the manoeuvres as second nature. Similarly, in motor racing you must know all about the limits of adhesion – different bends have a different limit for each bend; how to correct or get out of a skid; about braking distances; and about over-steer and under-steer which will affect the handling characteristics of different types (those with the engine in front or behind; front wheel or rear wheel driven) of motor vehicles. The Mini Cooper under-steers because it is a front wheel driven car. But most other cars over-steer because they are rear wheel driven.)

>>>(Not know much about motorsports, but the Judge’s reply to the (interview) question offer tremendous worth in a take-away.)

just the other day, i had to reply someone that i did not ask for an answer cos i did not know a question existed in the first place! :)

This person here is a physician (a specialist)in Malaysia for the past 33 years.

The retired justice's (NH Chan) book named 'How to judge the judges' this person read it in a current manner.

That this person need to find Justice NH Chan is imperative,

Can he find the retired justice's house (address) in Ipoh (or maybe receive email address.

My honour. Thank you.

Dr. Mydin

This gent demonstrates he knows his stuff by minute details and correct terms used… not ambiguous bragging… definitely not loyarburok stuff.

Funny ! "If you want to stay alive jam on the brakes and turn the steering wheel to the left".

Good wife or not, not for us to decide BUT she definitely listens, which is a good point all things considered.

Wishing all, Loyarburok team and Justice NH Chan especially, a healthy, successful and prosperous year ahead.

1) the rogue judges KNEW what they were doing. not that they are ignorant of the law. they chose to be BAD judges.

2) all these boil down to ketuanan melayu. everything has to do with ketuanan melayu. and money. lots of money. illegal money.

4RAKYAT

It boils down to ENGLISH…..basic English grammar and spellings..Cheers to your honour !!! It's my honour to read your piece. It's music to my ears and inspiration to my thoughts..Alas, so many Malaysian judges are just making noise and writing 'Malaysia Boleh English' judgement. I wonder what has happened to Justice K N Segara [a friend of mine]…he is being sidelined for being too JUST I presume?…cheers again old gentleman.

Judge,

You rock man.