This is the second in a three-part weekly series which provides an overview of the due diligence process: the different types of due diligence, why it is important, the reasons it is often done badly, and how to do it well. LoyarBurokker Marcus regularly contributes to The Edge Malaysia, where this serieswas previously published as “Counsel” in its “Forum” section.

Last week in Part 1, we established the meaning and importance of due diligence as well as some reasons why it is often poorly executed. These issues were examined in the context of due diligence conducted as part of acquisitions, joint ventures, investment decisions, business expansion and capital market proposals. We also touched briefly on the three different types of due diligence: legal, financial and commercial.

This article will provide an overview of the legal due diligence process – how it is usually structured and coordinated practically – and highlight the most crucial areas to be considered.

Coordinating due diligence

The scope of a due diligence exercise depends on several factors, such as the size of the transaction, the confidentiality of the deal, the industry in which the business is and the friendliness of the parties. However, there are some commonalities.

The due diligence process is usually driven by a legal adviser. This is probably out of practicality rather than necessity. For example, in an acquisition, the lawyers would be preparing the transaction documents, and the scope of the terms and conditions, representations, warranties and disclaimers may have to be adjusted based on the findings of the due diligence.

In a capital market proposal, the “principal adviser” would be a merchant bank, but it is the lawyers who prepare the planning memorandum, agenda, materiality guidelines, scopes of work and ultimately, the due diligence working group report.

In a typical legal due diligence exercise, the lawyers will draw up and submit a list of preliminary inquiries tailored for each transaction. The responses to the inquiries can, in the hands of an experienced and knowledgeable lawyer, prove invaluable in flagging potential key issues that may need to be thoroughly scrutinised. A comprehensive list of due diligence inquiries also helps to focus the minds of the people providing the documents or information to be reviewed and reduces the possibility of oversight.

Key areas in a legal due diligence

Using an acquisition transaction as a guide, the following are the areas that one would expect to be covered in a normal legal due diligence exercise:

- Corporate information. This provides a good understanding of the basic corporate structure of the target company and the entire group of companies – subsidiaries, associated companies and other interests (including options) held by the group of companies or its directors. It involves a review of the memorandum and articles of association and other statutory corporate documents. Crucially, it also includes looking through the minutes of meetings of shareholders, directors and committees. The information gleaned from the minutes books may have an impact on the other areas in the exercise as a whole.

- Business activities. Before the due diligence, an investor or purchaser would naturally have an idea of the business of the target company. A due diligence would uncover a comprehensive list of business activities, trading partners, territorial rights, products and services, licensing, agency and distribution arrangements as well as suppliers, manufacturers and customers. This would go beyond the surface-level information and involve a review of the precise written terms and conditions of the said business activities.

- Material contracts, including borrowings. Existing contracts are valuable to an incoming purchaser and a purchaser will need to be certain of the terms of these contracts and that they will continue to be valid after the acquisition. The issues surrounding contracts are vast enough to be the subject of a separate article. A common issue is determining whether a change of ownership nullifies the contract or whether prior consent is required. The amount or scope of any security deposit, advance payment or indemnity given should also be carefully considered. Another issue that can arise is where a service agreement with a government body may not necessarily carry over into a changed ownership. Many successful businesses are built on repeat transactions grounded on goodwill or mutual understanding, without a binding written contract. It would be foolhardy for any purchaser to acquire a company that runs its core business in this way. It would be similarly negligent for an acquirer to buy his way into being bound by performing services or selling goods to a third party on commercially unfavourable terms. The bottom line is this: A purchaser needs to know the contractual obligations, restrictions and entitlements that will be in effect once the acquisition is completed. Every single contract that affects the target company’s performance or profit estimates must be reviewed extensively.

- Litigation. An investigation will be conducted to discover whether the target company is the subject of any existing, or threatened, litigation actions. Any undisclosed litigation discovered may affect the pricing of the deal, or at least result in an indemnity being given by the seller for the potential costs or damages.

- Personnel. It is important to know the employment terms of key personnel, especially in relation to remuneration, length of employment and termination provisions. Additionally, a purchaser should not be caught by surprise by agreed personnel arrangements such as policies in relation to benefits, retirement plans, bonuses, insurance, severance packages as well as trade unions and work councils.

- Real property. Land and buildings are potentially one of the most valuable assets in any transaction. In addition to confirming beneficial and registered ownership of the properties, a due diligence should also include an investigation into any encumbrances, restrictions in dealings, third-party occupiers, access roads, details of outgoings, utility supply contracts, potential disputes and valuation reports or depreciation schedules.

- Intellectual property. The extent of intellectual property due diligence depends on the nature of the business. The main concern would be the protection of the name under which the business is carried out. A basic review would cover the documentation evidencing trademarks, trade names, copyright or patents that have been registered, rejected or are pending. Arrangements with third parties should also be reviewed to ensure that any intellectual property is protected by confidentiality or non-disclosure agreements.

- Compliance with laws. Companies have to be licensed to carry on their business. The buyer’s lawyers should ensure that the company has not done anything that would result in the revocation of any essential licences. In particular, compliance with guidelines or conditions issued by regulatory bodies, such as the Securities Commission, Bursa Malaysia, Bank Negara Malaysia, the Foreign Investment Committee or the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, should be confirmed.

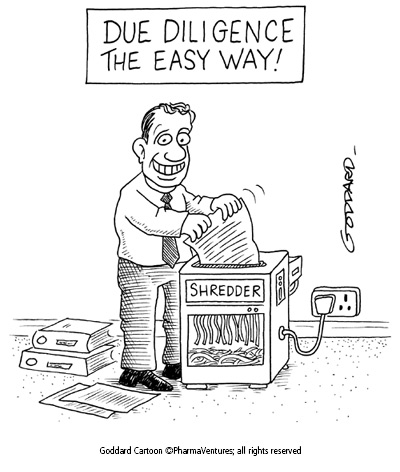

There are many other areas that can be investigated as part of a legal due diligence. They may appear to be very basic, but there are a surprising number of transactions in Malaysia that run into difficulties pre and post-completion due to shoddy due diligence work.

The underlying principle is always to conduct a review of the target company that is sufficiently inquisitive to uncover any hidden skeletons. With the legal report in hand, together with the results of the financial and commercial due diligence exercises, a purchaser should be able to say with the utmost confidence that he is walking into the deal with both eyes open.

Next week, this column will discuss the intricacies of commercial due diligence, which in many senses transcends the scientific and objective analysis of legal and financial due diligence.

LB: Marcus van Geyzel is a corporate/commercial solicitor in Kuala Lumpur, who tweets as @vangeyzel and blogs at marcusvangeyzel. Recently, he drank a tainted pint (or five) of Guinness, and ever since then he is occasionally mind-controlled to contribute to LoyarBurok. His interests are varied, but has a penchant for debates about culture, politics, football, and the idiosyncrasies of human interaction. He believes that the only certainty in life is that everything can be explained by the transperambulation of pseudo-cosmic antimatter.

Look out for Part 3 next week.