A consideration of the Thailand Family and Community Group Conference as a method for dealing with youthful offenders and its suitability for implementation in the Malaysian criminal system.

Roughly three and a half years ago, in the hustle and bustle of Bangkok’s swarming streets, 14-year-old Wit [alias] was snatched up by police for stealing 10 kg of spool of electrical wire from his employer. He spent that evening in a police lockup, agonizing over and replaying the moments leading up to his ultimate decision to commit the offense.

If this had happened to Wit four years prior, in 2003, life after arrest would have looked much differently. He would have been implanted into a criminal justice system arcane and intimidating to most children, and been subjected to court proceedings that would have disrupted his education, family relationships and cohesion with society. Moreover, he would have likely had to serve a sentence in a juvenile detention center, which tends to have enormous and debilitating repercussions on children, most importantly because of a child’s developmental vulnerability to such harsh environments.

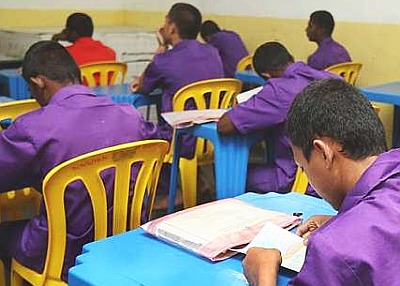

Fortunately, Wit did not have to endure that timeline of hell. Rather, after he was arrested, he was diverted to Thailand’s Family and Community Group Conferencing (FCGC) program. This novel approach, spearheaded in 2003 by Thailand’s Department of Corrections after observing the successes of New Zealand’s Family Group Conferences, aims to innovatively deal with minor child-offenses. The FCGCs are designed to divert children away from the traditional justice system and place them in counseling sessions that usually involve the offender, victim, respective families and members of the community. The conference, focusing more on the victim’s needs, affords every participant catharsis by permitting them an open and safe environment to speak about their feelings surrounding the incident. Ultimately the discussion, which is facilitated by a trained social worker, leads to an agreement on appropriate reparation that satisfies the victim and community, while instilling a valuable lesson in the offender.

In Wit’s case, the conference consisted of himself, his parents, the house owner from which he robbed the spool, a local community leader, the arresting police officer, prosecutor, psychologist, social worker, and an officer from the Department of Juvenile Observation and Protection. After a grueling discussion and formal apology, all parties decided it best that Wit repair the harm by doing community service of his choice – scouring and maintaining the central Mosque in the Bangkok suburb where he lives.

If Wit had entered into the formal justice system – court and detention – the damaging consequences would have been rampant and compounded. Here are some of the most salient and documented trends resulting from early child detention: intense stigmatization from the community and family, weakening self-confidence, lack of economic output into society, and a recidivism rate that turns children into hardened criminals.

Indeed, many of these responses to imprisonment occur in adult offenders. However, the effects on children are magnified because of the facts inherently associated with youth – lowered developmental capacity and heightened vulnerability to the long lasting effects of traumatic experiences. They are undergoing a critical developmental stage in life, one that will determine how they will gradually mature, which makes it ever the more pivotal that they are handled with the appropriate care to enable reintegration into society once an offense is committed.

And there are some cold-hard statistical findings to back this argument up in Thailand. Of the offenders who participated in the conferences, less than 4% have reoffended as compared to the recidivism rate of 15-19% for juvenile offenders prosecuted in court. While it can be argued the court-prosecuted children are more prone to committing offences again because their cases tend to be more violent, the finding is nevertheless not insignificant – children are responding to these conferences in ways unheard of in the traditional justice system.

So it begs the question: if Thailand, a country ranking below Malaysia in almost every judicial, economic and developmental indicator in existence, can adopt such a logical policy towards child-offenders, why hasn’t its southern neighbor followed suit?

As an NGO officer/journalist/traveler/makanan pedas aficionado sent here to document the project of Dato’ Yasmeen Shariff, a lawyer awarded a fellowship from the Geneva-based international NGO International Bridges to Justice, this is exactly what I was tasked with covering. And sadly, over the past three months, I found no good answer to my aforementioned question.

Currently, Malaysia has no system in place to divert child-offenders away from court proceedings, and certainly is not equipped with robust conferencing programs like those in Thailand. Dato’ Yasmeen won the 2010 JusticeMakers grant to address this inadequacy by introducing diversionary alternatives to court proceedings and detention, alternatives that would be tailor-made for each specific case.

She set me up with spectrum of interviews to get a good grasp of the current state of juvenile justice in Malaysia, including Director General of JKM Dato’ Meme, former SUHAKAM member and child psychologist Datuk Prof Chiang Heng Keng, KL Legal Aid head Stephanie Bastion and the Minister of Information, Communication and Culture Dato’ Rais.

The meetings elicited two conclusions.

The first is that you must make an important distinction, to a certain extent, between a defective system and the people that work within it. Most welfare officers, lawyers, and NGO staff toil day-in-day-out, with the resources they have, to make children’s lives better. Sometimes this doesn’t always appear true because of the daily media headlines that incessantly highlight the worst in our society. But these stories are the minority, and they unfortunately obscure the noble work being done by men and women every day in this country to help children in need.

But the second, more disturbing and disheartening finding, is that no one really has a good idea why this policy is still on the shelf. Literally everyone I talked to had the same response: “yes, Malaysia should introduce diversion,” or “We have been talking about adopting diversionary alternatives.” However, they all blurted out perfunctory statements as to why it has not happened – inter-agency coordination problems, lack of training, and, the most nauseating response of all, lack of money.

So let me get this straight: you have the money and resources to haphazardly and expensively (detention is invariably more expensive then the proposed programs) lock children away for petty theft or not carrying an identification card, but the thought of diverting those resources to more effective and rehabilitative programs doesn’t muster much force?

I never really got to the bottom of this enigma; merely scratching the surface of what could be a deep and complex systematic black box that I may never wholly understand. Who profits from the current system? The always elusive “powers that be”? Or is it simply a matter of convenience in dealing with a demographic that lacks voting power, and consequently the ability to influence political decisions and policies?

I don’t want to espouse any far-fetched conspiracies because that kind of vitriolic discourse rarely begets substantial and healthy solutions. But what I can say for certain is that children keep flowing into the Malaysian justice system and getting flushed out further damaged and demoralized, without any explanation of whom this system is benefiting. I know it doesn’t happen often, but it might to prove a little valuable to take a look up at Malaysia’s northern neighbor and see how they run things.

To read the full story of Wit, documented by UNICEF, go here.

To read a report on Thailand’s FCGC and their results, go here.

To read more about my work with Dato’ Yasmeen Shariff go here.

Liam Hanlon hails from the inner city streets of San Francisco, where he served as a full-time Mexican-food aficionado, part-time social activist, and even smaller-time student. After attending UCLA for his bachelor’s degree in Political Science, Liam moved to Geneva, Switzerland for a year, working for the international legal-rights NGO International Bridges to Justice. During this stint, he co-coordinated the 2010 Asia JusticeMakers Competition, which sourced and funded local legal-rights initiatives throughout Asia. After a two month hiatus scouring the lands of Southeast Asia with his rucksack, Liam moved to KL in October 2010 to begin documenting the work of one of the JusticeMakers Fellowship receipients, Dato’ Yasmeen Shariff, for her work with juvenile justice. He has since shifted his to time to another NGO Voice of Children, as well as transforming into a LoyarBurok minion.

Hey Liam,

Thanks for the response. I'm very interested in Restorative Justice the after reading about the Truth and Reconciliation process in South Africa. Really opened my eyes on how reconciliation can be for the better.

I have special interest in juvenile offenders as I grew up among some of them. Though I disagree with the path that they have taken, I think young offenders needs to be given a second chance as they deserve it and have a future. The realities of life is harsh and these kids are victims of a vicious system. Unfortunately, the status quo in the Malaysian system doesn't permit that. Mixing juveniles among other juveniles perpetuates this vicious cycle where crime is the only resort, even after their time is up.

I think a reformation is needed to ensure a better future for them. I'am not 100% against retribution. I believe that punitive measures, (which I consider a form of evil) be kept to a bear minimum (say community service or apologies/reparations). It mustn't be physical (caning) or jail time.

On the rezoning program that I mentioned, I believe that part of the problems which juvenile offenders face is due to the environment that they grew up in. The chances of a kid committing crime in say, ghetto areas is higher than in suburban areas. Peer pressure plays a part and if offenders are relocated in better communities, hopefully they would shape out for the better.

Relocating them to better communities offers an opportunity for them to rehabilitate to the max and are able to practice counselling and moral values in reality than only learning it in theory.

I understand your concerns that separating the kids from their families might have negative effects on them. But maybe, in some situations, their families are part of the problem. Maybe the kids were abused or were not given enough attention from their parents. Bad parenting plays a part in shaping the world view of these kids and might be a reason why they did crimes. When a kid with bad parents watches kids with good parents having it easy, he becomes inferior and out of that inferiority, he commits crimes for the attention or for wanting material goods. This is just on top of my head. But the point is, in some situations, offenders requires a new environment to reform themselves, hence relocating them to charity homes.

I'm extremely interested in pursuing this concept for juvenile offenders and am looking forward to do it once I graduate. But best of luck!

Yo yo yo batu 5,

Thanks for your engaging comments and interest in the issue of restorative justice. I am in total agreement with you regarding your main points – the current tendency towards punitive responses for juvenile offenses needs to be dramatically shifted to adapt a philosophy of restorative justice. This paradigm shift, happening with more frequency throughout Asia, will reshuffle the priorities of the juvenile justice system in Malaysia: it will no longer adhere to abstract and conceptual notions of punishment that we commonly associate with the criminal justice system, but rather take a logical, moral and pragmatic look at what judicial processes, responses and programs will best serve the needs of rehabilitation for the child and retribution for the victim. I know you are a little bit wary of the word “retribution,” but I think it is a pivotal aspect if we want the offender to realize the consequences of his/her offense, as well as ensuring the victim gains closure, who often is also a child.

Secondly, I also concur with your criticism (if I understand it correctly) of housing minor offenders with more hardened juveniles. There is a multitude of research material that concludes mixing nonviolent and emotionally unstable offenders with violent offenders runs a huge risk of turning the former group into more hardened criminals. Furthermore, I think this theory is compounded when it relates to child offenders, taking into account their nascent developmental stage.

It is of paramount importance that when a juvenile reaches this crossroad – after committing his first offense and making first contact with the judicial system –the judicial system handles him/her EXTREMELY carefully and thoughtfully. Without oversimplifying the point, the court has basic two options, with actual, tangible programs running the spectrum from end to end.

The first would be to take punitive action, placing the child in some form of detention that will most likely catapult him into much higher levels of crime and delinquency. He will associate with other offenders, and through constant implicit and explicit reminders, come to think of himself despairingly as simply a prisoner – nothing more, nothing less. The second choice, and the approach both of us are promoting, would be through restorative justice. This would focus on how to best position the child to reintegrate into society, addressing his/her issues in a constructive and self-affirming way. Hopefully people in power begin to realize that the former will not suffice in dealing with this generation of “problem children.”

I have not heard much about the rezoning program you mentioned, although I do have some initial thoughts. I imagine it would weaken familial cohesion, as the child would be separated from the family. What kind of lasting effects do you think this would have?

Thanks for the words of encouragement. Let me know if you want to chat about this more.

Hello Liam,

I agree with you that a form of Restorative Justice should be implemented among juvenile offenders instead of the Retributive Justice system where the focus is on retribution. We need to look at the needs of these misguided offenders instead of this unhealthy obsession with punishment.

Juvenile Offenders are in their formative years and are capable of being corrected. By making them languish in jails or mixing them with other juveniles, the effect of counseling would be lost as they only are able to learn it in theory instead of practicing it practically, as they are isolated from civil society.

Currently, Juvenile Offenders are placed at correctional centers such as the Henry Gurney School in Malaysia. I feel that being incarcerated and mixing with other juvenile offenders might worsen the situation as they might be mixing with worse characters.

I also believe that the focus on juvenile offenders should purely be on rehabilitation. Retribution should only be left to a bare minimum (like apologizing, making reparations , community service like what Wit did). I think its contradictory to punish a person on one hand and tell him to "be good" on the other hand. The message of rehabilitation would be rendered ineffective when you punish an individual.

I suggest that most Juvenile offenders be relocated to "white areas" or areas where crime is minimal, to maximize the effects of rehabilitation and isolate juvenile offenders from each other. Relocate them to Charity Homes/ "Rumah Pengasih" maybe.

I understand this might sound radical, but I'm very interested in restorative justice and rehabilitatio soundn instead of the old 'eye for an eye' concept. Keep up the good work!