Why being in remand is worse than being in prison, the desperate acts some will do to get out of being in remand and how a legal aid client out manoeuvred a volunteer lawyer.

A person held in remand is best illustrated by contrasting them with someone who is ‘out on bail’.

When someone is accused of an offence they usually can apply to the court for bail. ‘The Court have always leaned in favour of admitting an accused person to bail’: per Wan Yahya J in Public Prosecutor v Dato’ Mat Safuan [1991] 2 CLJ 1112. The police can also grant bail before an accused is produced in court. The court, is not bound to, but will usually set a sum for bail. In rare instances, bail is rejected. If an accused person deposits the bail sum set by the court (with the requisite guarantor(s)) he would not be detained by the police or prison authorities i.e. remand. He would be free as any normal citizen.

If he cannot afford bail, or his application is rejected, an accused person will be held in remand. And such a person should be distinguished from someone imprisoned. For those in remand, the court has not made any pronouncement of their culpability for the offence unlike those imprisoned where the court has found them guilty.

If you were unaccustomed to practicing criminal law like I was early in my practice, it is likely you did not appreciate these fine distinctions between those held by ‘the authorities’. Like me, you would have also assumed that all those detained in whatever capacity were accustomed to the same living conditions. And those conditions were somewhat decent, or at worse tolerable.

I have since discovered these ideas to be completely and utterly untrue. Not that I have experienced it but simply from the frequent complaints about the conditions I have heard from my legal aid clients. To illustrate just how disparate the living conditions are between those in remand and those in prison, let me tell you about a legal aid case of gang robbery that I handled several years ago.

It was a strange case because my client was the only one charged for committing a gang robbery (section 395 of the Penal Code, 20 years, fine and/or whipping) with the 6 or 7 others allegedly still at large. He was accused of committing gang robbery against a gentleman in a public area.

His story was that at the material time he was a drug addict. At the time of the offence he had taken a hit and was high basking on some stairs out in some public place in Kuala Lumpur. Some men were robbed where he was spacing out. He didn’t know who they were. Somehow he got picked up and charged for the offence. His story seemed true because the police didn’t find any of the victim’s valuables on him and he didn’t know who those 6 or 7 others were. He couldn’t even make them up to save his life.

If that was his story then it was obvious he had nothing to do with the gang robbery. My usual advice is if you didn’t do it don’t plead guilty. The worse thing is to be convicted and bear the punishment of a crime that you didn’t do.

Strangely, right from the start this particular client expressed an unusual keenness to plead guilty to the offence. Explaining the repercussions and the dire consequences of pleading guilty did not have the intended effect on him.

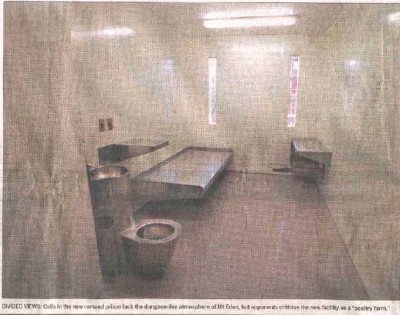

When I asked him why he wanted to plead guilty, he explained the conditions in remand were so terrible that he wanted to be put in prison where the conditions were better. The food was better. The detention cell was not so overcrowded and cramped. He hated it there. That is why he wanted to plead guilty. I asked him how he knew about this and he replied that he had 3 previous convictions for drug possession and his experience has shown this to be true. While I certainly could not contradict him factually, I was nonplussed.

I never expected anyone would want to go to prison for a crime they did not commit. I was very concerned and spent the rest of our interview trying to convince him out of this mad scheme. We would fight it quick, I promised him, so he wouldn’t spend a day more than was necessary. We would grill each and every policeman on the stand to prove his innocence. We would leave no stone unturned in his defence. By the end, I succeeded. He claimed he saw my point and agreed to fight the case. I left him a little more at ease.

On the mention date, I arrived in court early because I had one other mention in the civil courts before I could attend to his case. I registered my name with the police officer and informed the interpreter to stand down the matter until I arrived. He was brought early so we managed to speak before I left to sort out the civil matter. He confirmed his intention to fight the case and said he was fine about my attending to the other matter first.

I got back by about late 10 to the courtroom during the second round of calls for the cases and informed the interpreter of my attendance so she would call up the case. When it was eventually called up, the Judge looked at me and said, ‘Rayuan?’ I was taken by surprise and felt betrayed. Let me explain why.

‘Rayuan’ translated literally from Malay means ‘appeal’. What is meant is that the accused person’s counsel is invited to submit on the mitigating factors the court should consider before deciding the sentence for the offender. It should be appreciated at this juncture that a submission for mitigation is only made after an accused person has pleaded guilty. That means my legal aid client managed to get his case called up before I arrived, pled guilty then stood down the case (a short adjournment of a half hour or so) for me to submit on his mitigation. Very cunning!

Confronted with this I asked the Judge for a moment to confer with him to confirm his instructions. When I approached him, it was obvious he was pleased with himself. He was smiling and nodded affirmatively when I asked him whether he was sure he wanted to plead guilty. Feeling crestfallen I returned to my chair and conducted his mitigation, but could not shake the sense of unease that pervaded me.

He got X years. I went over to the lock up before I left just to ask him why he did what he did. I think he could appreciate I was bewildered at what had happened and so attempted to explain. Though these are not his actual words (since he spoke Malay), this is the gist of it:

‘I know you think I should have fought this case. You have good arguments. Maybe we will win. But I don’t want to wait a few years in remand only to lose. You see. People like us will never win. Long time ago I fight my case and lose. And the conditions in remand are very bad. You don’t know how bad it is. It is better in prison. Conditions are better and cleaner. For people like me, either I go in now or I go in later. So better I go in now. Anyway, don’t worry. The food is better. At least now I don’t have to always look for something eat.’

He thanked me for my efforts.

Fahri Azzat is without actual remand or prison experience (except as a visitor) unlike his more learned friends Amer Hamzah and Edmund Bon. He has no plans in the near or far future to obtain such experience. He has no plans to write a scintillating best selling novel about prison life in Malaysia although he has sketched an outline on a napkin somewhere.

I have a story to tell. My husband has been taken in for Kidnapping case which he was not invovled in just happened to be there when the flat was raided. The real culprit got away my husband taken in for 2 offences 3 off kidnapping and 2 of handling weapons. He has been in remand for a month today. Currently situated in Sengai Bloh Jail. I have struggled to bail him out as I do not have access to his orginal passport. I am not allowed to have access to his fones so I can search for his friends numbers who has his passport. The bail amount is 11,000rm which I can not afford I am trying to appeal to reduce the amount. I have been in Kuala Lumpur for almost 2 weeks now with a 10months baby who my husband has yet not seen. I was looking to settle here in Kuala Lumpur as my husband is a business man for almost 5 years now. I visted my husband today and wanted to cry my eyes out. He has been sick for almost 2 weeks and he has yet not seen a doctor even after so many request. I put a complained to one of the officers at the reception and the response I got is everyone is ill what can we do?? they dont care for your rights in anyway. My husband was saying he has been put in a small room with 7 others where the bathroom is one to share between and in open they have to bath. They eat in the same room as well. How un-higenic. No wander you can end up being rapers between each other as you naturally become mentally sick. I have a bail date this monday very desperate for a good solictor who can request the magistrate to bail my husband out with the orginal passport. Any one out there to help or guide me? This my 1st time with the laws of this country and tell you the truth it really has put me off to even visit here on holiday. All comments welcome.

Dear Hussain, I am sorry to read about your husband's predicament. I know this is no consolation but how he is being treated is no better than what Malaysian citizens have to go through. You're right – the police and/or prison authorities don't care for your rights. I would suggest you try asking around at the Bar Council Malaysia (www.malaysianbar.org.my) or try the Bar Council Legal Aid Centre (Kuala Lumpur) (http://www.kllac.com/). I am sorry to learn that your experience in our country has been such a miserable one. I certainly wish much better for both you and my fellow citizens. All the best.

I went to prison occasionally (also as a visitor), specifically the prison for juvenile offenders.

I go, talk to them, and hear tons of sad stories. Indeed, I even regard few of them as my friends. It just that, for caution, not everything they told is true.

I recall my first time when I go to prison and one of them asked me whether I'm afraid, and I said no. Simply because they all are very nice and warm towards me. This is what this fella replied,

"hati-hati sikit, dorang ni semua ada dua muka (buat-buat gelak jahat)"

and me, senyum kelat.

Now, after almost two years going to prison occasionally, I guess he's right. I know it's like no point telling this, I just wanna share my story dealing with them, and how innocent looking these prisoners can be.

Fahri Azzat thanks for sharing!i never thought that remand would be worse than going into prison.The guy choose to go prison than remand.i felt bad for him because he admitted crime that he did not committed.but is the remand condition still that bad NOW?

Karl, I tell you a lot of the legal aid cases are heartbreakers. There is little justice for the poor and marginalised.

Pei Ling, for sure. For example, I am certain Dato' Seri Anwar Ibrahim was treated way better than 99% the other prisoners in Sungai Buloh.

June, thanks! It is. That's what saddened and challenged me at the same time.

Fahri, enjoyed the narrative but felt so bad for the guy! I hope he's still at peace with his decision. It's a harsh world when choosing prison is a better alternative than being free.

Guys, the police remand system is different than the ones operated by the Prison Dept. Both are equally bad though…

Story goes to show, it's a different set of ethics and logic for those person's (allegedly) "on the other side" of the law.

Thanks for sharing important stories like this, I've heard other stories too, about the police treating educated / politicians differently if you were uneducated / poor in remand or prison. I heard Suhakam does human rights sensitisation workshops for the enforcement forces including the police but obviously it's a huge project to sensitise the entire police force…

Did my comment just go missing? I remember trying to post it twice, beneath Andrew's.

I was referring to how it is just as bad in the US, where prisoners's rights are not respected. Things are not necessarily better under remand either, because of overcrowding. Brutality to those under remand is not unheard of. In 2003, there was an act that was pssed against prison rape as American prisons (well not only the Americans) is well-known to be a violent place with more than 10% of rapes occuring in prisons to both sexes (what you've watched on TV about being a prison bitch is true).

At the same time, in some circumstances, especially for those in very dire conditions, being in prison is sometimes safer than being on the streets. And sometimes, being in prison means having a roof over your head, at last. Moreover, certain marginalized groups never actually got access to education and living skills until they end up in prison (as I mentioned in my 'cerpen' ;)), though I have no way of telling if every prison system in the US have the resources for educating their prisoners.

Of course, race and class is also a factor when it comes to remand procedures…

"At least now I don’t have to always look for something eat."

Ah heartbreaking lah.

Holy f…