Did he jump, was he pushed or was it all an accident?

The man fell from the window of a law enforcement agency. The officers said it was a suicide. The inquest decided that it could have been an accident, apparently discounting the possibility of either suicide or homicide. Upon investigation by a judge the officers scramble to produce versions after versions of the story, blatantly contradicting the facts and each other in the process.

The deceased’s demeanour was first described as troubled, then calm; in order to spin a story they might as well have said that they all burst into song with the deceased out of joy and camaraderie.

Desperate to extricate himself from the hot seat, each officer attempted to establish that he was not responsible for the death, that he was only doing his job as told, he was absent from the scene at the time, as if a person who planted a bomb in a bank must be innocent because he was not there when the bomb exploded. The interrogation techniques revealed — physical and psychological abuse, pinning guilt on the deceased on the basis of no evidence — were horrendously inhumane.

The journalist questioned indications pointing against the theory of suicide: the parabola of the fall, the absence of fractures on the wrists, the conspicuous neck injury appear to suggest the deceased was unconscious when he fell. Ridden with suspicion from the beginning, the answer to ‘who did it’ had always been obvious. The question that remains is: How did he die?

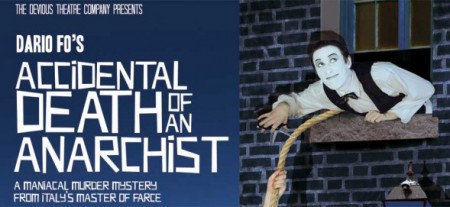

Of course, I am referring to the Accidental Death of an Anarchist, a play written in 1970 by Italian Nobel Prize winner Dario Fo, as performed by the Corpus Christi freshers in Cambridge. I’m sure you wouldn’t have thought of anything else. Right.

The play was inspired by a real man, Giuseppe Pinelli, who fell to death from the fourth floor window of a police station in Milan back in 1969. Along with other anarchists suspected of setting the bomb that killed 17 at Piazza Fontana, he was held and interrogated without trial. His name had since been cleared. Police officers described his death as a suicide; legal proceedings investigating his interrogators concluded that it was accidental. All of a sudden deaths from falling out of windows had become hauntingly familiar to us.

42 years ago the Italians may never have imagined that it would recur, but here we are again, waiting for another judge to decide whether it could have been an accident.

The play opens with the fact that an anarchist had fallen to death from the window of a police station. While in the station, a Maniac — certified crazy, 16 times over — chances upon the opportunity to impersonate a judge, and proceeds to question the officers involved in order to ‘investigate’ the anarchist’s controversial death. The police offer various ‘corrections’ and ‘rewrites’ of their testimony as more flaws are exposed, providing contradictory statements (“But you remarked earlier ‘fear of losing his position, of being fired, definitely contributed to the suspect’s suicidal breakdown.’ So, one minute he’s smiling and the next he’s a desperate man.”), and churning out fantastic ideas (to give you a rough idea, “I tried to hold him back when the jumped, but I only caught his foot and his shoe came off! I even have the shoe here with me.” “Did the anarchist have three feet? When he fell, he had two shoes on.” “That’s because one foot was bigger than the other, so he wore a big shoe over his small shoe over his smaller foot. For aesthetic purposes.”), perhaps almost as fantastic as an attempt to strangle oneself with your own hands. Almost, but not quite.

The Maniac’s statements about scandals are particularly relevant to us Malaysians, the rakyat who get an overdose of scandalous allegations ranging from submarines that wouldn’t submerge, jets that couldn’t fly (no engine maybe?), to a whole array of sex videos. Everybody loves a scandal, but it doesn’t always follow that the actors will be held responsible, or that justice will be served. “So, who gives a damn? The important thing is that the scandal breaks out — nolimus aut velimus! So the Italian people, like the English and Americans, will become democratic and modern; and so they can finally exclaim, “It’s true, we’re up to our necks in shit, and that’s exactly why we walk with our heads held high!'”

The average citizen has nothing to gain from a scandal, aside from the wicked satisfaction of denouncing prominent figures in the corridors of power; but the authorities have everything to gain, for scandals are — the Maniac describes — the “fertilizer of Western democracy… the antidote to an even worse poison: people’s gaining political consciousness.” By providing a brief outlet for the public to vent their dissatisfaction which then dissipates quickly, they allow the status quo to be re-established. “Do not forget that,” the Maniac hence reminds us, and at this moment his 16 previous medical records of psychological disorder doesn’t matter anymore, “in the stench of scandal, all authority is submerged. Let scandal be welcomed, for upon it is based the most enduring power of the state!”

Admittedly, Dario Fo had a penchant for left-wing, anti-authoritarian messages. But what if he was a Malaysian? What if his inspiration came from the events of July 2009? Fo’s plays are meant to provide opportunities for adaptation to reflect local issues. What if we substituted every reference to the police with the anti-corruption agency, the fourth floor with the fourteenth floor, the anarchist with a political secretary? Will it be banned? Will he be arrested for sedition or detained as a potential threat to national security? Will he have to sign a statuatory declaration to emphasise that he was contemplating a wholly untrue scenario?

Admit it — when you read the first paragraph were you tempted to warn me to shut up? I suspect it is going to be difficult to dismiss his story as nothing more than deliberately left-wing, anti-authoritarian fiction.

There are lines that send a shudder up my spine. The part where the Maniac, impersonating as a judge, tells off the police officers: “You know what people think of you by now? That you’re a bunch of bull-shitters… as well as bad boys. How can you expect anybody to believe what you say anymore?” The part where the ‘judge’ offers advice to help the police weave a plausible story, and the Chief replies, “I’m sincerely touched. It’s wonderful to know that the High Court is still the police department’s best friend!” Suddenly it is almost impossible to imagine this performance being allowed back at home.

Remember how, as kids, we used to poke fun at a friend without directly mentioning their name, waiting for them to take the bait, jump in and defend themselves, and look stupid for being overly sensitive? Seemingly innocuous words are offensive only when the listener can personally relate to them. Were this farce of police brutality, abuse of power and lack of judicial integrity to be performed in Malaysia, I doubt we would be proud enough to have a genuinely good laugh.

Because we are afraid that those comedic moments might possibly even have a grain of truth in them.

Some parallels are too irresistible to draw, indeed so many that once too often in the midst of roaring laughter from the audience, I found tears inexplicably stinging my eyes. This was meant to be a ridiculous slapstick, farcical and satirical. And yet when the characters, the lines, the details appear to blend into and superimpose upon the very faces we see on national newspapers, every joke seems too real to be funny.

So if you’d misdirected yourself in the beginning, categorising it as fact rather than fiction, I can hardly blame you. Sometimes I can’t help but wonder if, at the end of the day when the truth comes out — if it ever does — the only difference between this particular performance and our grim reality is that in the former, at least there’s a gorgeous inspector.

tried our best to get siuyea to say something, and he wrote a piece titled "Saying I love U to Ibrahim Ali". http://katasayang.wordpress.com/2011/06/29/saying…

siuyea also has a piece that summarizes a short book written by John Slimming. Check it out to find similarities between how John Slimming described May 13, and how our Bersih 2.0 has been unfolding…

http://siuyea.blogspot.com/2010/04/malaysia-death…

I often don't bother leaving comments, but this article is very well-written and thought-provoking. Kudos and thanks Low When Zhen for this beautiful piece. Looking forward to reading more from you.

Good stuff, keep it up. Malaysia can certainly gain from insightful, charming and intelligent writers such as yourself.