In our Selected Exhortations category, we republish interesting stuff such as must-read articles and essays not originally written exclusively for the blawg, and which have come to our attention. Please feel free to email [email protected] if you would like to reproduce your writing, but first follow our Writer’s Guide here.

This speech was originally published here.

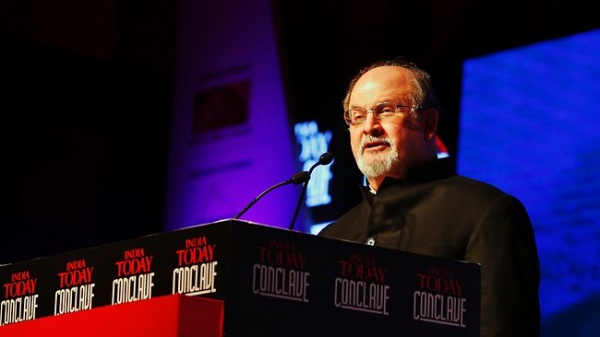

First, I’d just like to say I’m very happy to be mentioned in the same breath as Saadat Hasan Manto, a writer that I admire enormously and who has been so well translated recently into English by Aatish. I have always revered the work of Manto and learned a lot from it. I have to thank India Today, because they have given me this opportunity, the last opportunity (Jaipur) having fallen away. They called me and suggested that we needed to put that matter right, and that this would be a way of doing it. I was really happy and grateful to be given the platform. So thank you very much to everyone involved with the magazine.

And so here I am. Two months ago, on Indian television I promised that I would be here and here I am; and you would have noticed the lack of protests or even interest from the people who were supposed to take an interest and protest. Even after various generous members of the press called them up and asked them why they were not protesting or interested. In spite of that, they didn’t protest and they seem not to be interested. So that’s good. Well, most of them, except for Imran Khan, and various politicians who appear suddenly to have discovered that their schedules were really crowded.

Actually, I have to thank Imran Khan for this platform, because I was going to speak at another session – a less important one. This was going to be his chance to talk to you; so I guess I have been promoted. So, I thank him for vacating the spot and allowing me to occupy it.

You know, there was a time when I would have felt very uneasy indeed to face Imran Khan… on the cricket pitch. I was never a very good player of fast bowling, or slow bowling, or any speed of bowling in between. But times change; and now it seems that it is Imran who is afraid of facing my bouncers. Maybe his hook shot is no longer what it was.

I want to make a number of points about this. One is that Imran has not been entirely straightforward. He has said that he only found out a couple of days ago, when the full programme was issued and my name was on it, that he realised he couldn’t come. This is not the case. Imran was told by India Today on February the 28th, who the leading speakers at this conclave would be, and that one of those was me; and he made no negative response. He was given the list of speakers again four days later, including my name; and he made no negative response. So, it is not true to say that he was not told until the day before conclave that I was coming.

Let’s be fair. Imran is a man of the old school. Maybe he doesn’t understand how this new-fangled stuff called email works. Maybe he doesn’t know how to open his email box and see what messages are there. Maybe he doesn’t even have anybody to read it for him. Poor man. But this man wants to be the ruler of Pakistan! Maybe familiarising himself with these new-fangled technologies would be a good step on that road.

Also as Machiavelli could have informed him, if you want to lie to placate some mullahs you depend on, don’t leave a paper trail that proves you lied. That’s just careless.

Seriously: Imran said, or his spokesperson said on his behalf, that he wouldn’t dream of being seen with me because of what he calls the immeasurable hurt that I have caused to Muslims. I would like to look at that phrase “immeasurable hurt” in the context of the real world. In the real world, I would say “immeasurable hurt” is caused to the way in which Muslims are seen by the terrorists based in Pakistan, who act in the name of Islam, including those who attack this country from Pakistan, backed by the Lashkar-e-Taiba, with whom Imran Khan now wants India to sit down and talk.

And “immeasurable hurt” is caused to Islam by the presence in Pakistan for so long of Osama bin Laden, and by the opinion polls which show that 80 per cent of Pakistanis see Osama bin Laden as a hero and a martyr for Islam; and by the recent evidence provided by WikiLeaks from the emails hacked from security firm Stratfor, which show that the Pakistan Army and officers of the ISI were in regular contact with Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad.

“Immeasurable hurt” is caused to Islam by people like the fanatic who killed this young man (Aatish Taseer)’s father and by those who showered the killer with flower petals when he came to court. Immeasurable hurt, Imran? This kind of hurt is measurable.

In the real world, Muslims in both Pakistan and India suffer from enormous economic hardship, from bad education and shortage of opportunities. The repressive consequences of Islamic extremism on women and of mullah-driven politics on the freedom of the citizens; these things are what Muslims actually face in the real world. And Imran Khan would do well to speak of the “immeasurable hurt” caused by these things, and not take the demagogue’s route of choosing instead to demonise a book written 25 years ago, and making its author a bogeyman with which to distract his audience from the “immeasurable hurt” of their actual lives.

And what is true of Imran is also true of seminarians of Deoband or any of the other people presenting themselves as spokesmen on Muslims’ behalf who seem more interested in highlighting these culture wars than looking at the realities of lives of Muslims in the subcontinent.

By the way, The Satanic Verses is a book which I would be willing to place a substantial bet that Imran Khan has not read. Back in the day when he was a playboy in London, the most common nickname for him in the London circles was ‘Im the dim’. The force of intellect which earned him that nickname is now placed at the service of his people, and its enemy, it seems is my book. If Imran really wants to argue about the literary merits of The Satanic Verses, I am happy to meet him in a debate on that subject anywhere and any time. Well, maybe not anywhere.

If he is not prepared to engage me, maybe he should just pay attention to the difficult job he has set himself. He is trying to play a very difficult game placating the mullahs on the one hand, cosying up to the Army on the other while trying to present himself to the West as the modernising face of Pakistan. That’s difficult. I would concentrate on that Imran. Trying to keep those balls in the air, it’s not going to be easy.

This is what we call the exercise of freedom of speech. It feels pretty good.

This word, freedom. It’s a beautiful sounding word, isn’t it? Who would be against freedom? It’s a word everyone would automatically be “for”, one would think. A free society is one in which a thousand flowers bloom, in which a thousand and one voices speak. And what a simple and grand idea that seems. It’s like that copper goddess standing in the harbour, enlightening the world.

But in our time, many essential freedoms are in danger of defeat and not only in totalitarian or authoritarian states. Here in India also, a combination of religious fanaticism, political opportunism and, I have to say, public apathy is damaging that freedom upon which all other freedoms depend: the freedom of expression.

I have to apologise for being one of the subjects of this argument. Ideally a writer should not be the subject. A writer should be an observer, not the observed. The writer should be the person discussing not the person being discussed. But circumstances once again dragged me onto the stage recently – or rather, in Jaipur, prevented me from taking it. As we now have a couple of months of perspective, it’s pretty clear that what happened there was some predictable Deobandi bigotry pandered to by the Congress Party because of what turned out to be pretty useless electoral calculations by the Congress Party. It didn’t even work, Rahul. Years and years of kneeling down to every mullah you could find, and it didn’t even work. You must feel sick.

In the debacle of Jaipur it was suggested that for me to turn up at all was wrong. This is a case of the world turned upside down. What‘s happening here, tonight, is what I would call ‘normal.’ A writer of Indian birth, who loves this country, who has spent much of his life writing about it, shows up to talk to an Indian audience about India. I would call that normal. What is abnormal is for that to be prevented. And we seem to be in danger of getting this upside down.

And it’s by no means only about me. I was extremely shocked at Jaipur when writers who stood up for my work, were not defended by the Literary Festival, and remain, at this point still in danger of prosecution for what that they did. This in spite of the fact that people have read from The Satanic Verses in India many times since the book came out in 1988, without any question of prosecuting them. And despite the fact that the only prohibition for The Satanic Verses is a customs ban; a typically Indian piece of sleight of hand. Don’t actually ban the book, just stop it coming into the country. In theory, somebody could print the novel in this country. There is no law against it. Any publishers interested? See me later.

You can download the book. This ban is an absurdity in the electronic age. And yet it exists and there are four writers who maybe in danger of prosecution for having read aloud from the novel, while the men who threatened violence go free.

Jaipur itself is just an incident. But its important as an indicator of what’s becoming more and more commonplace in India, which is a culture war, a war against cultural artifacts of all kinds, films, works of visual art, literature, all different kinds of theatre, and this is carried out well by the general public, mostly sits by indifferently.

At the time of the European Enlightenment in the 18th century, the great writers and intellectuals of that movement, Rousseau, Voltaire, Montesquieu, Diderot, knew that their real enemy was not the state but the Church. Earlier, when the mighty Rabelais was under fire from the Church, it was the King of France who defended him on the grounds of his genius. What an age that must have been, in which a writer could be defended because of his talent! After Rabelais, the 18th century writers of the Enlightenment insisted that no Church, even a Church with an inquisition at its disposal, could be allowed to place limiting points on thought. The so-called crimes of blasphemy and heresy were the targets because those were the methods used by the Church to limit discussion; and the modern idea of free speech was arrived at by defeating the notion that these were offences and that these could be used as ways of silencing expression.

Now, there is a tendency to say, “That’s a Western idea. That’s not how we think over here.” But the Indian tradition also includes from its very earliest times, very powerful defences of free expression. When Deepa Mehta and I were working on the film of Midnight’s Children, one of the things that we often discussed was a text dear to our hearts, the Natya Shastra. In the Natya Shastra we see the Gods being a little bit bored in heaven and deciding they wanted entertainment. And so a play was made, about the war between Indra and the Asuras, telling how Indra used his mighty weapons to defeat the demons. When the play was performed for the Gods, the demons were offended by their portrayal. The demons felt that the work insulted them as demons. That demoness was improperly criticized. And they attacked the actors; whereupon Indra and Brahma came to the actors’ defence. Gods were positioned at all four corners of the stage, and Indra declared that the stage would be a space where everything could be said and nothing could be prohibited.

So in one of the most ancient of Indian texts we find as explicit and extreme a defence of freedom of expression as you can find anywhere in the world. This is not alien to India. This is our culture, our history and our tradition which we are in danger of forgetting and we would do well to remember it.

There was an article I just read in this week’s The Hindu newspaper which reminds us that S. Radhakrishnan would talk about how many of the earliest texts of Hinduism do not contain the idea of the existence of God; and contemporaries of the Buddha, quoted also in this article, would say that there is no other world than this one, and would deny the idea of a divine sphere. So again, in the oldest parts of Indian culture, there is an atheistic tradition in which the ideas of blasphemy and heresy have no meaning because there is no divinity to blaspheme or be heretic against. This is our culture. This is not an imported culture. It’s not alien to the Indian tradition. This is the Indian tradition, and those who say it’s not are the ones who deform that tradition.

These ancient sages thought, and I think, that God is an idea that men invented to explain things they didn’t understand. Or to encapsulate wisdoms that they wanted to capture. That Gods in fact are fictions. So when there’s an attack by Gods or their followers on literature it’s as if the fans of one work of fiction were to decide to attack another fiction. It’s as if the revolutionary followers of Arundhati Roy were to take up arms against the old school charms of Nirad Chaudhuri and declare him to be… improper. Fictions should not go to wars. There is room on the bookshelves for all of them.

I remember within my living memory, an India in which my parents’ generation were very very knowledgeable about the culture of Islam, Hinduism so on; but would nevertheless sit around in the evenings and tell jokes, satirise and poke fun at and debunk certain aspects of religion; and there was no sense that something shocking or wrong was being done. This was just normal, everyday conversation.

As a young person in both India and Pakistan (because my family was equally divided between India and Pakistan), I heard in many gardens in the evenings people sitting around having fun with the ideas of their cultures and of their faith. And this was not considered to be a crime.

The idea that this is somehow wrong has crept in much more recently and does great disservice to all of us. What are the weapons used to impose this idea of wrongness? Of course, the old weapons of blasphemy and heresy are still there. But there are two new weapons, which are the ideas of “respect” and “offence”. Now, when I use the word respect, it means that I take people seriously. I engage with them seriously. It doesn’t mean that I agree with everything they say. But now is that the term respect is being used a way of demanding assent. “If you disagree with me, you are disrespecting me. And I will get very angry and may even pick up a weapon; because that’s my way when I am disrespected.”

A culture of “offendedness” is growing up, not just in this country, elsewhere too, but very much in this country, a culture in which your “offendedness” defines you. I mean, who are you if nothing offends you? You’re probably a ‘liberal’ — and who would want to be that?

The fact is that in any open society people constantly say things that other people don’t like. It’s completely normal that that should happen and in any confident free society you just shrug it off and you proceed. There is no way of creating a free society where nobody says things that other people don’t like. If offendedness is the point at which you have to limit thought then nothing can be said.

Behind these ideas of “offendedness” and “respect”, there is always the threat of violence. Always, the threat is that if you do that which that disrespects or offends me, I will be violent towards you. So the real subject is not religion, it’s violence and how we should face up to the threat of violence.

Recently in India, there have been religious attacks aimed at many of the arts. We know some of the big headline cases. We know about the Hindu mobs who destroyed the set of Deepa Mehta’s film Water, the production of which was delayed for many years and eventually took place in Sri Lanka. We know, as Aroon Purie mentioned and as I said two years ago, when I was speaking from this platform, about the shameful treatment of Husain Sahab, an artist who should have been revered by this country, who was instead driven out of it. We know the craven behaviour of Bombay University when some Sena apparatchik attacked Rohinton Mistry’s novel, and the book was immediately removed from syllabus. We know the dreadful behaviour of Delhi University which withdrew the classic essay of A.K. Ramanujan, 300 Ramayans, because a few Hindu hooligans decided that it was anti-Ram. We see these things happening almost every day. We see a gay artist being attacked in a gallery by Hindu thugs. These are the cases which make the headlines. But it seems that almost everyday now somewhere in India there is a piece of bullying by Muslims or Hindus of creative artists whom they accuse of offending them.

Voices are being silenced. Publishers are more frightened to publish. Galleries are more afraid to display certain kind of art; certain kind of films would not be made that might have been made 15 -20 years ago. The chilling effect of violence is very real and it is growing in this country.

And the other part of this story involves all of you. There is a public apathy towards these attacks. We approve of the great technological and industrial and economic growth of our country but we don’t seem to value our cultural artifacts in the same way, even though, the greatest thing about India history is the incredible richness of the Indian artistic and cultural tradition. The contemporary manifestations of that seems to be neglected; and these ideas, the ideas that you should not upset people, you should not upset religious interest groups, these have quite broad acceptance in the public mind. Who gives you the right to upset people? I would say “Who gives people who claim to be upset, the right to come and attack me and my fellow artists?”

I repeat: the subject is not disagreement. The subject is violence, and the threat of it, which prevents dissenting voices from speaking.

That’s what is going on and people here are asleep, I think. Very largely asleep to what’s going on and you need to wake up.

There is a line in my novel Shalimar, the Clown in which one character says to another, “Freedom is not a tea party, India. Freedom is a war.”

You keep the freedoms that you fight for; you lose the freedoms that you neglect. Freedom is something that somebody’s always trying to take away from you. And if you don’t defend it, you will lose it.

I have this theory that the Indian electorate is smarter than the politicians and sees through them. Yes, people can sometimes be whipped up, as they were by the religious extremists in Jaipur. But how many people? How big are these mobs? How representatives are they? It seems to me that 95 per cent of the Muslims in India are not interested in the violence being done in their name. And that would be true of the Hindu community too. Because as I said, people actually have real concerns. Real concerns about their real lives. This is what preoccupies them. How to get an education for their children, how to have good homes to live in, how to get a job. These are the things that concern people in this country. Not these absurdly demonising attacks on works of art.

These attacks, whether upon my book or people’s films or plays or paintings or whatever, these are not things that come from the bottom up. There are not such great public objections to this kind of work. These attacks are created from the top down. There people at the top who think they can get some benefits by whipping up and inflaming various situations, and who use their positions in order to do so.

The people are more sensible than their leaders. India deserves to be led better than it’s being led. It deserves leaders who can bring her back to the non-sectarian, non-communal land which the nation’s founders envisaged. And here, at the gatherings like this one, the idea of that India can be, not so much forged as renewed. Forged anew. And it can be done only if all of us have the ability to speak our minds.

To speak freely without fears of religious or governmental reprisals. The human being, let’s remember, is essentially a language animal. We are a creature which has always used language to express our most profound feelings and we are nothing without our language. The attempt to silence our tongue is not only censorship. It’s also an existential crime about the kind of species that we are.

We are a species which requires to speak, and we must not be silenced. Language itself is a liberty and please, do not let the battle for this liberty be lost.

Didn't the great Anuar Ibrahim who was in Delhi recently, also avoided the same event which Saman were to participate, for the same reason Imran Khan avoided.

An excellent piece by a freedom fighter. The next world war is really the fight to freedom of expression.